Major Alexandra Kafka Larsson addressing the Defence Intelligence Executive Track at the ESRI Conference 2015 in San Diego.

From Military Intelligence to AI: A Personal Journey Through the Evolution of Digital Research

A few months into my training at one of the first classes of the Swedish Air Force Intelligence School, I found myself assigned to give the weekly intelligence briefing to my classmates. I had access to classified intelligence reports about events unfolding in Russia, and I remember wondering: How were these reports actually produced? And what would be the best way to present them with proper context?

I’d had my first Mac for six years by then, so doing everything on paper already seemed outdated. Little did I know that question would shape the next three decades of my professional life.

The Foundation: Learning to Separate What Matters

During our training, we learned about the intelligence cycle and what each step contained. But what struck me most was realizing that good analysis requires mastering three distinct skill areas:

- Information management and analytical methods – keeping track of all data and the methods for analysis and dissemination

- Knowledge of collection systems – understanding where to get data and what’s accessible

- Domain-specific expertise – deep knowledge of the subject area itself

This separation has stayed with me ever since and has profound implications for how we think about software support for analytical work. Each area needs different types of tools and approaches.

“Good analysis requires mastering three distinct skill areas: information management and analytical methods, knowledge of collection systems, and domain-specific expertise.”

We were taught to separate judging the reliability of sources from the credibility of the information itself. We learned to make assessments based on facts and never say things we couldn’t back up. These knowledge bases came from classified binders or commercial references like Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft.

But I could already see the potential for something more.

Bridging Two Worlds

The logical next step was academia. I wanted to see what parts of academic research methods could develop my skills as an intelligence officer. I studied intelligence analysis at Lund University, East European Studies, Russian language, and eventually Political Science.

What struck me during these political science courses was how much time we spent on scientific methods and different methodological approaches. I saw the merit of combining the academic and intelligence worlds to increase the quality of analysis.

But I also noticed a fascinating gap: the military world wasn’t always aware of available scientific data, while the academic world was naturally unaware of a nation’s collection capabilities. As an intelligence officer, you could theoretically task collection of new data, whereas political scientists had to work with what was publicly available.

“The military world wasn’t always aware of available scientific data, while the academic world was naturally unaware of a nation’s collection capabilities.”

The academic rigor of providing references was critical in academic writing but wasn’t considered mandatory in the military world, often citing source protection concerns. I began to see how bridging these approaches could strengthen both.

The Technology Promise (And Reality)

I immediately saw the benefits of storing information digitally for easy access and repurposing. Initially, I focused on building a local digital library on my computer. Then networks and broadband internet opened up a new world of search and possibilities.

I felt frustrated that we only had general-purpose office tools, but implementing specific analytical processes required extensive manual work. We saw advanced document management systems, geospatial software, and graph-oriented analysis tools emerging, but they operated in silos, making holistic data processing flows difficult.

That’s why I felt incredibly fortunate to be put in charge of an unclassified international effort to develop information management methods and software tools. What became known as the Concept System for Intelligence & Security was born at the national C2 lab in Enköping.

There, we truly understood the merits of integrating systems using common data models and immediately saw the links to methods and teamwork. The structure for storing information objects needed to reflect organizational needs and required capabilities.

We ran groundbreaking experiments—20 video streams in a single digital meeting in 2006, something that seemed revolutionary then but is now normal for millions worldwide. We worked on separating reasonable predictions (based on data) from efforts to increase understanding of interconnected forces to prime decision-makers for various scenarios.

The computer scientists wanted to introduce Bayesian theory-based software to support analytical work. We developed structured ways for analysts to set up indicators for trigger points and define what concrete data was needed to confirm each indicator.

Methods were converging, but around 2010, the technology stacks weren’t quite ready to make this vision reality.

New Domains, Familiar Patterns

After leaving the Armed Forces, I wanted to understand civilian analytical methods, so I studied trendspotting and environmental analysis. I was presented with a toolbox that felt familiar but had new names and focused solely on public data:

- Source scanning inventory – consciously reflecting on where we collect data geographically, societally, linguistically

- PESTLE analysis – categorizing data and conclusions about external forces

- Horizon scanning – structured ongoing establishment of baselines and identification of weak signals

These tools seemed like more applied, practical versions of principles I’d seen in both academia and intelligence. But again, the lack of efficient digital tools meant building structures from almost a blank sheet of paper.

This strengthened my conviction that this invisible profession needs better tools that actually empower us to work according to best practices and established methods.

The Constants Across Domains

Looking across my journey, certain core principles have remained constant:

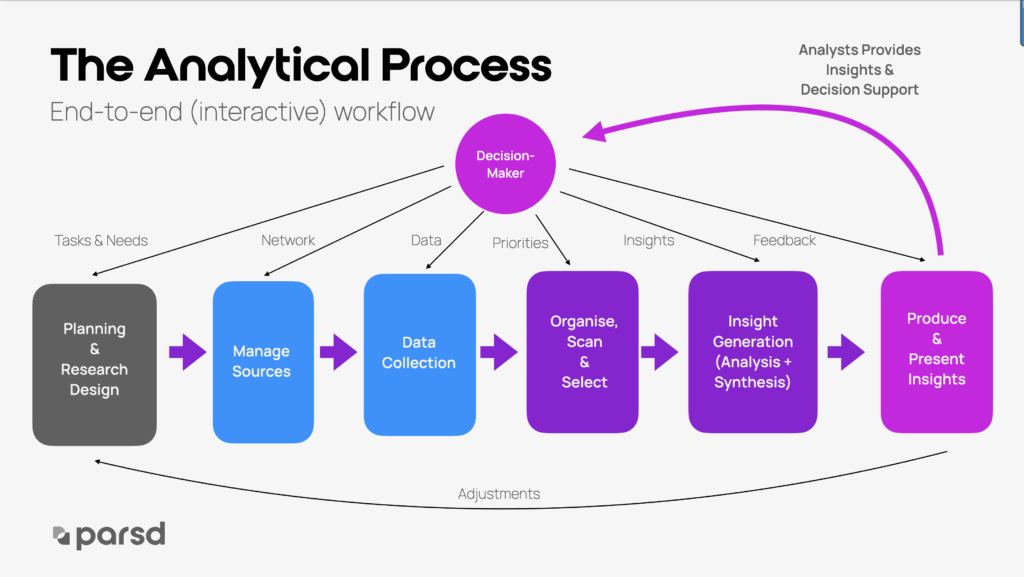

There are steps we see in all research workflows that need methodological discussion and software support:

- Planning & Research Design – often becoming task management for teams

- Source Management – tracking publishing sources separately from data collection

- Data Collection – actually ingesting data from sources

- Organize, Scan & Select – pre-processing before analysis

- Insight Generation – analysis and synthesis

- Produce & Present – adapting insights for specific audiences

Crucially, this isn’t linear but highly interactive with formal and informal feedback loops between analysts and decision-makers.

The AI Revolution and Its Implications

The major gap has always been our dependence on productivity suites like Microsoft Office, where unstructured documents and slides become the main format. Data in these formats lacks structure, making data-driven visualizations difficult.

The AI era is finally bridging this gap. Generative AI can now connect structured and unstructured data in completely new ways. Multimodal AI models can provide meaningful metadata for documents, images, audio, and video—something we’ve struggled with for decades.

But AI also poses significant challenges. In our new geopolitical landscape with hybrid warfare, AI tools can power disinformation in what sometimes feels like a post-truth society of fake news and opinions over facts.

This means we must rely more on curated trusted sources (like when the internet was young) combined with transparent methods that preserve digital provenance. We can no longer judge quality by looking at end products—we must focus on how insights were developed and whether we can trust the process.

“We can no longer judge quality by looking at end products—we must focus on how insights were developed and whether we can trust the process.”

Fighting for Democratic Values

To some degree, I’m building the tools I wished I’d had decades ago. But today, this quest feels much more important than personal convenience.

The integrity of facts and scientific methods needs defending to preserve free and democratic society. We need to support our invisible profession of analysts and professional thinkers with tools they deserve to contribute to preserving liberal democracy.

The rapid progress in visualization technologies also means we can create amazing interactive collaboration experiences while we try to save the world together.

Because that’s ultimately what this is about: ensuring that in an era where anyone can generate convincing-looking analysis, those committed to truth and democratic values have the best possible tools to create genuinely trustworthy insights.

“The methodology matters. The tools matter. And the invisible profession of analysis has never mattered more.”

The methodology matters. The tools matter. And the invisible profession of analysis has never mattered more.

What’s your experience with analytical methods in your field? How are you adapting to the AI era while maintaining methodological rigor?

Alexandra Kafka Larsson is the CEO and Co-founder of Parsd, a digital research platform that helps analysts create trusted insights. She has over 30 years of experience developing intelligence systems and methods across military, academic, and civilian domains.